This was a paper which I wrote as an extension of my research on classifying tactically interesting positions. Unfortunately I did not finish the project as I got quite sick at the end and after working for roughly 4 months between the two projects for probably 8 hours a day, I was done (also, towards the end of this I was beginning to explore the project which I’ve been working on for the last 6 months, brief explanation on that in my About page). I hope to eventually re-examine this problem as I just have a gut feeling that it’s possible to come up with a solid solution, I just needed time away from this area for a little bit.

During this class, I continued working on a previous project where I used an ensemble of ANNs and algorithmic methods to identify chess positions that appeared to contain a tactic but did not actually have one. My aim was to create a metric designed to quantify the difficulty of these positions. This proved to be an extraordinarily challenging task, as the way humans reason in chess is very different from the tools typically used for chess position assessment, namely engines. Unfortunately, I was unable to develop such a metric in the end. However, by taking unique approaches, I gained insights into the problem that may assist with further research.

To approach this, I first needed to understand the problem of chess position assessment. I defined the problem as follows: for any given position, its difficulty in terms of heuristic evaluation is determined by:

- How many lines there are to consider,

- How difficult each of those lines is to calculate, and

- How these lines compare to the objective best line given by the engine.

To solve this problem, I needed to address each of these components. To generate lines for consideration, I aimed to obtain a list of moves that aligned with the heuristic present. Since my tactic model is responsible for identifying whether or not a tactic exists, I utilized a method called Layerwise Relevance Propagation (LRP). This method propagates back from the classification of a tactic existing to the input layer, allowing me to see which elements of the input layer contribute most to the position being classified as a tactic. Once I understood which pieces contributed most to the classification, I could artificially boost moves involving those pieces. These boosted moves would become my selected moves, which I then would use techniques for line evaluation to assess their complexity. Finally, I would compare these lines to the objective best line.

Layerwise Relevance Propagation (LRP)

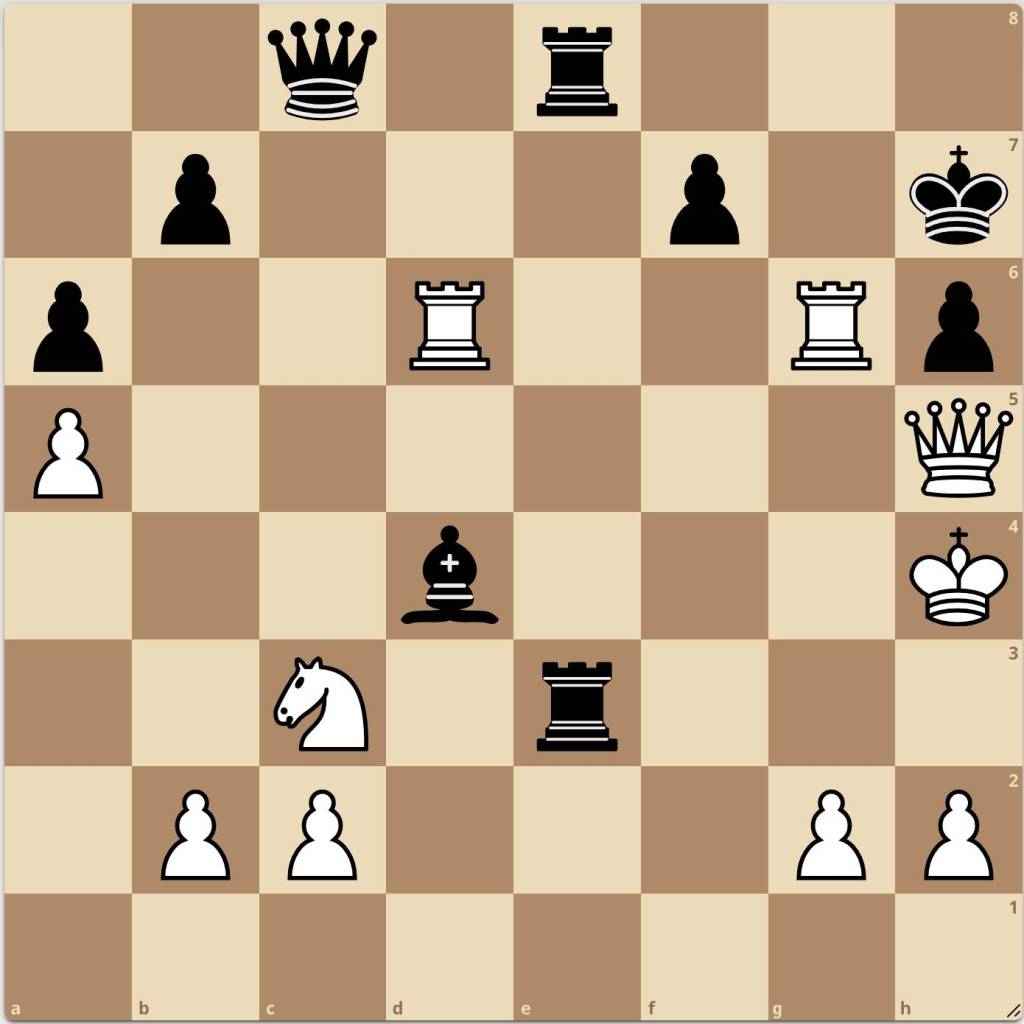

As mentioned, I was using a method known as LRP where you work backward through your neural network from the selected output received all the way to the input layer in order to understand the relevance of your inputs contributing to the final output seen. This can be formulated as:

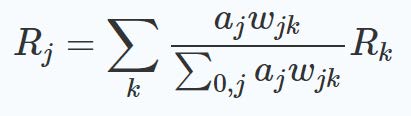

I built an implementation in Colab and tested it on a position. The position I considered was one which my model had identified as a checkmate for black:

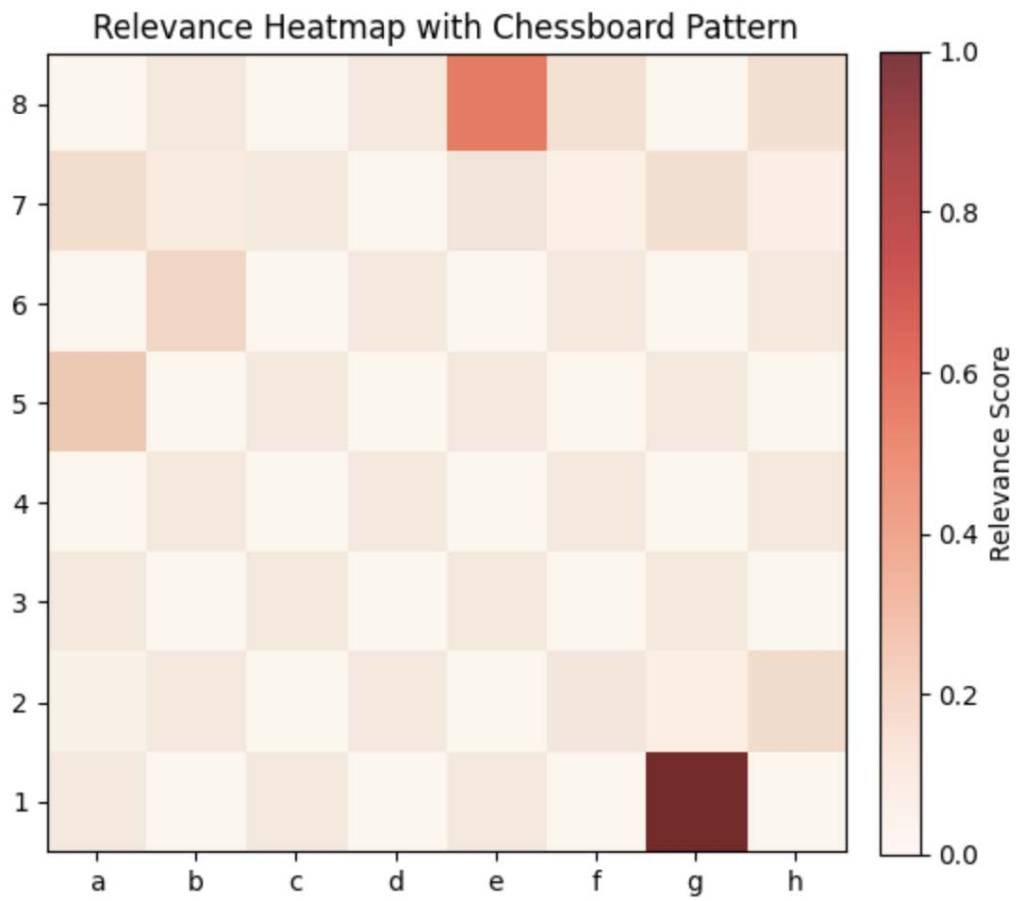

Right away, I was worried I had done something wrong due to the relevance being completely scattered and nonsensical:

Furthermore, I was seeing this type of visual being produced for basically every type of position we analyzed. After some thought, I decided to adjust the formula to perform what is known as zero-rule LRP. This involves eliminating all bias contributions, preserving only contributions due to activations. After this, I saw a much clearer picture:

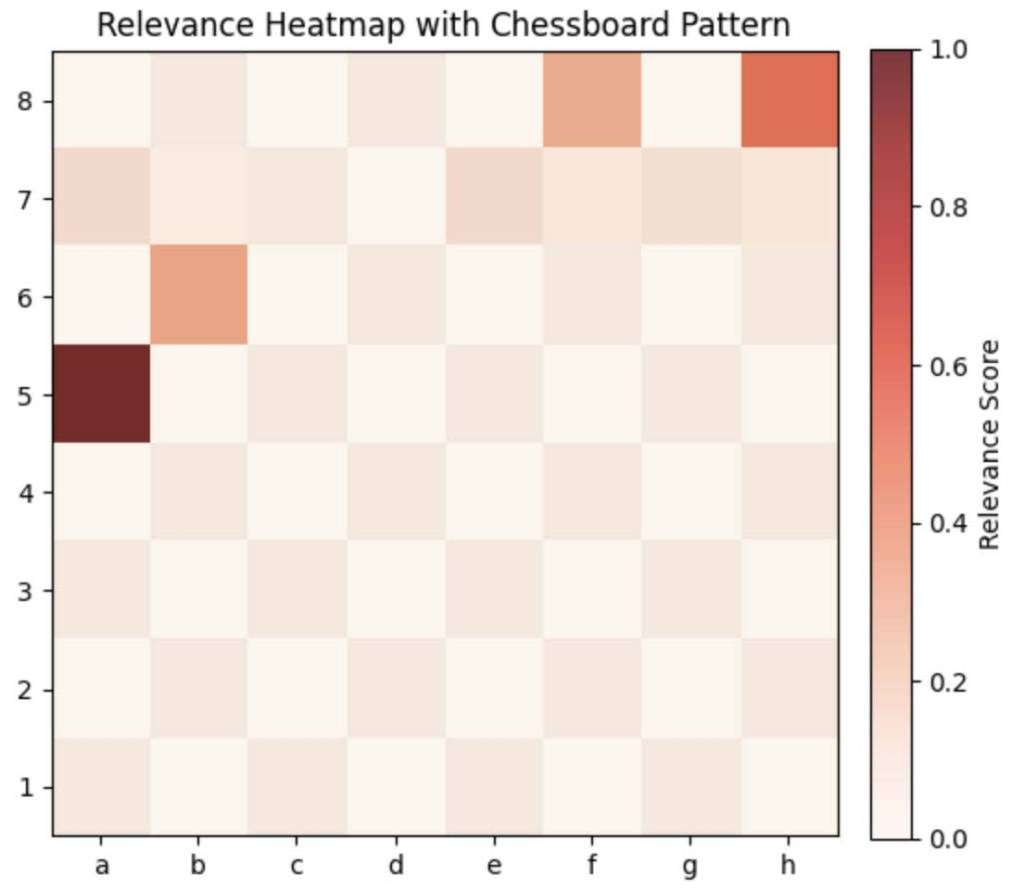

This classification of the pieces involved in the position for Black that contribute to a checkmate aligns perfectly with what would be logical to a human understanding the position. The queen on c8’s gaze intersects with the rook on e3 at the h3 square, directly below the White king. Interestingly, none of the White pieces contribute to the position being considered a checkmate according to my model.

I thought I was well on my way to solving the problem, but I noticed that this classification was still very unreliable. For some positions, the classification would be very reasonable, while for others, it seemed as though the model was classifying the position as a tactic for the wrong side. I tried making adjustments using something called gamma-rule LRP, which amplifies positive contributions. This method accepts a gamma parameter that controls how much these positive contributions are amplified. However, changing this value proved to be extremely unreliable and ultimately undermined my confidence in LRP working as expected.

To address this problem, I realized that my model needed to simultaneously consider whether a tactic was present and for whom the tactic was present. Initially, I approached this as independent predictions, using an output vector of length 2 and two sigmoid outputs instead of a softmax. Unfortunately, the results were unremarkable. I realized that the model’s insights into the pieces involved in the tactic were not improved by predicting the side independently.

Instead, I reformatted the model’s output to a vector of length 4 with dependent outputs for both the tactic and the side. Now, for the model to be correct, it had to predict not only whether a tactic existed but also the correct side. I believed this approach would align the model’s tactic predictions more closely with the correct side and reduce variation in the pieces identified as involved in the tactic. Unexplainably, this was not the case.

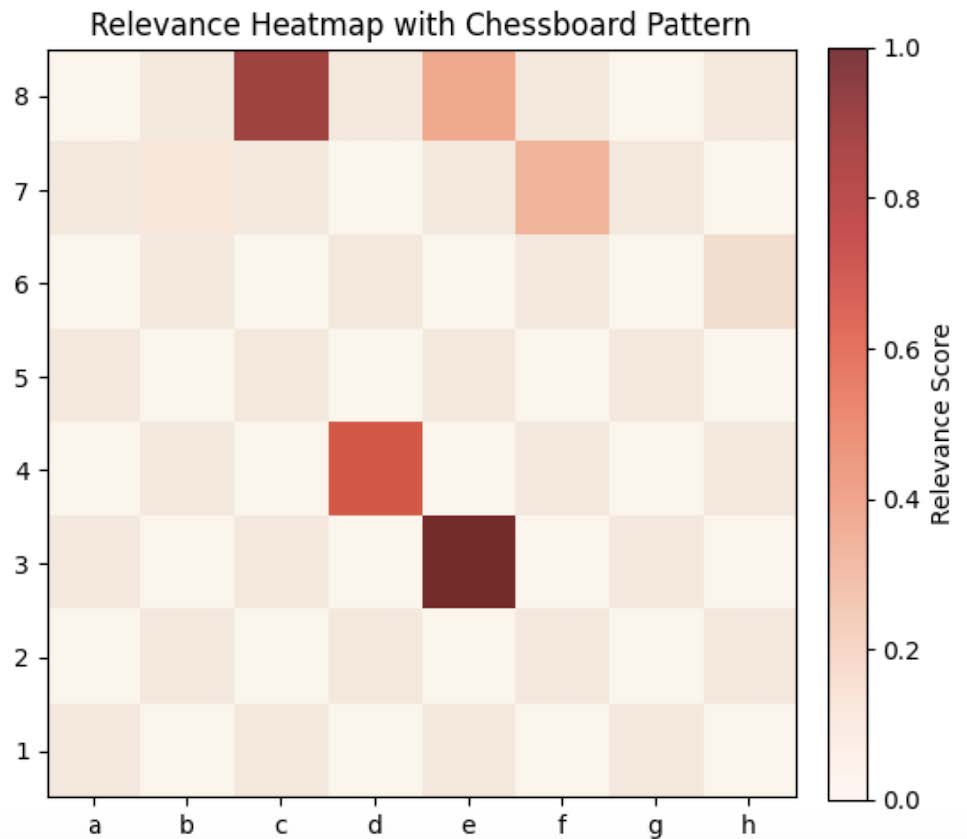

Here is an example of a position that my model identified as a tactic. Bear in mind that it is White to move:

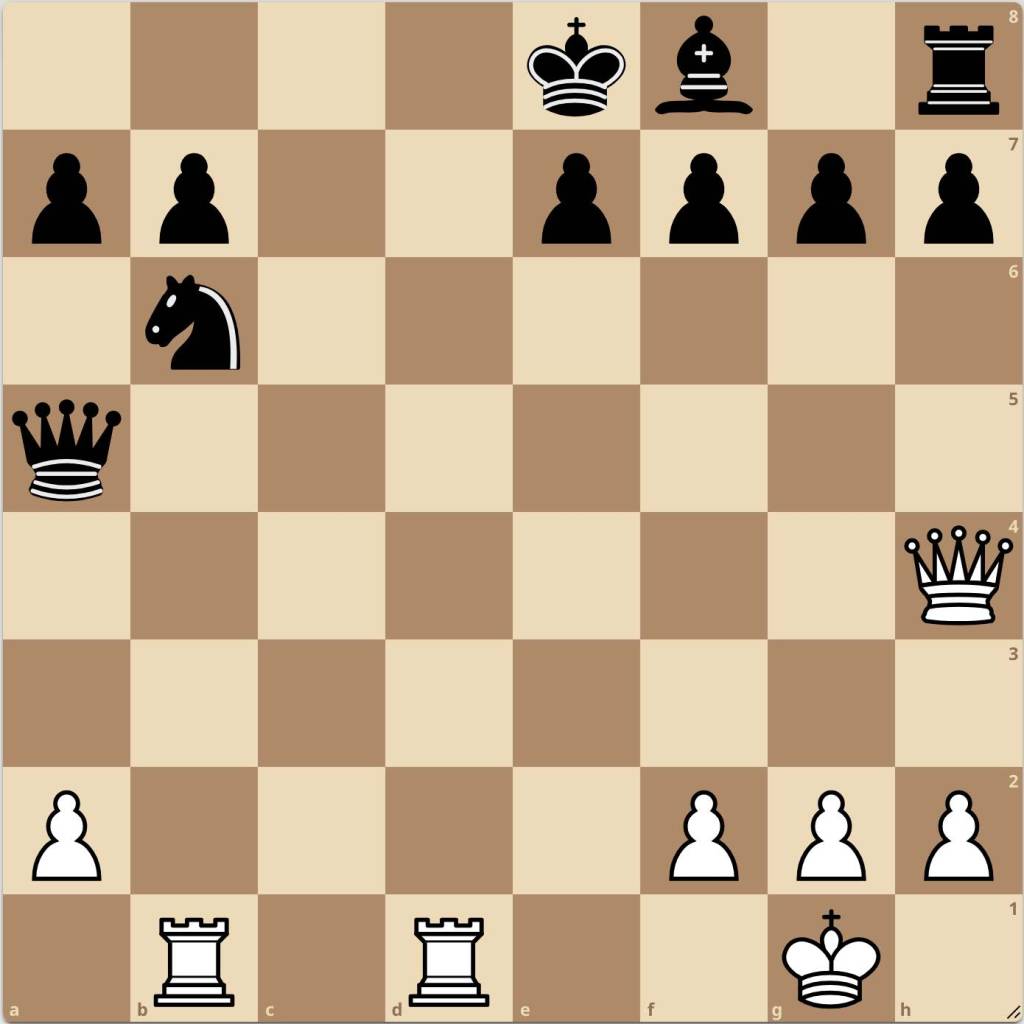

Now here is the mapping for my first model:

Now once I map using dependent model:

Because my models were not reliable in communicating what activated their classification on the input layer, I could not move forward with this as a method of analysis. Future researchers should note that this approach could still be a promising method for understanding neural network outputs in chess. I attempted to implement techniques for stabilizing output generation in the lower layers (closest to the input layer), but this was also unsuccessful.

Although I was disheartened by this result, I decided to press forward and try a new metric. My first goal, as planned, was to generate a list of moves from the pieces highlighted as important in the positions and then analyze those lines to determine their difficulty. I decided to explore engine depth analysis as a potential metric.

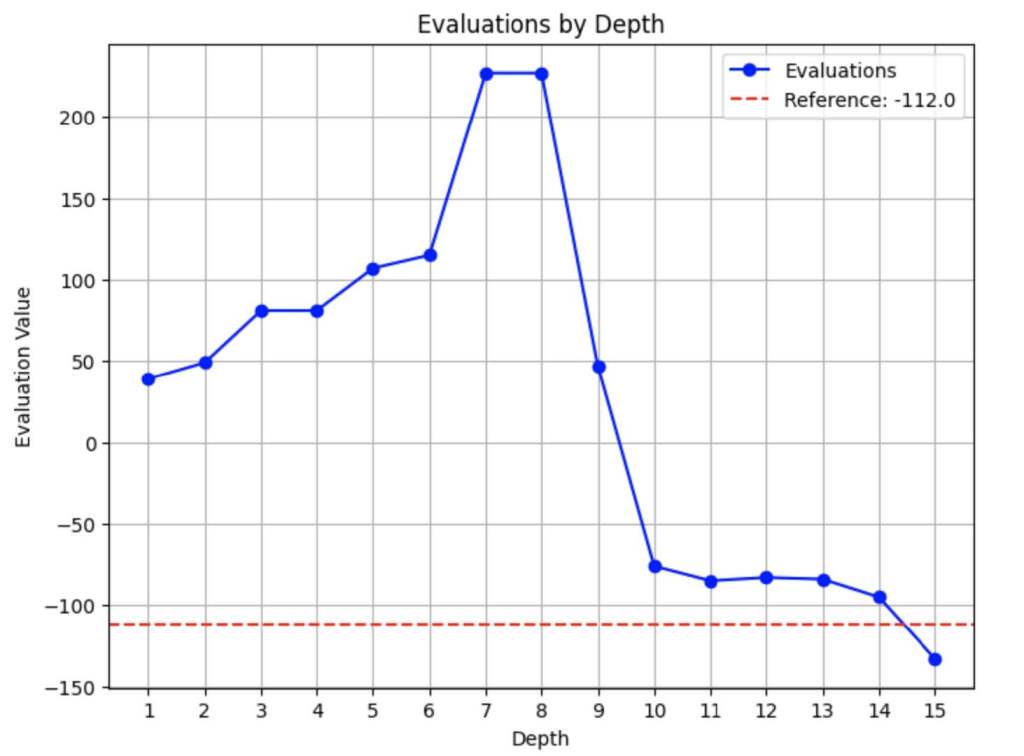

When running a traditional engine, depth refers to how many moves forward the engine is analyzing in a given position. Depending on the position, evaluation can change rapidly and

unpredictably as depth increases. This behavior as depth grows was what I wanted to investigate. By quantifying these changes in evaluation, I hoped to develop a metric that captures positional difficulty. Looking at the same position as above, here is how I quantified this behavior:

Here we see the evaluation of the position according to the engine as depth changes. Note that the eventual evaluation at depth 25 was the red dotted line. It was reassuring to see that there was consistently a large jump seen around depth 5 to 8 in our initially identified positions, meaning that many of our positions do appear tactically interesting around the same depth. My idea was to measure both the variance of the evaluation as well as the change in the evaluation at depth 1 compared to the eventual evaluation. Using this behavior, I could create some linear combination of features that translate to a scalar value useful as a metric.

Unfortunately this was as far as I was able to get during this quarter (I contracted pneumonia the last two weeks). The process taught me a great deal in terms of taking a very broad question such as quantifying heuristic difficulty and parameterizing it in a way that can be actually understood. My metric I feature-engineered originally called squared evaluation difference is the closest metric I have to a functional quantification of difficulty, and this does

represent the third component that I hypothesized as integral to the problem of heuristic difficulty quantification. While I was unable to finish the problem, I believe the approach I took was still the correct one and I believe the use of visual-based engines combined with new reasoning capabilities that are being implemented with transformers offers a significant opportunity to tailor many elements of the chess experience to humans and how we think about the game.

Leave a comment