This was the beginning of my 2 part project identifying tactically-interest positions using ML. It was extremely fun and made me realize how much I enjoy designing pipelines of this nature. I was working on this project alongside my friend Ayush Nair who provided us with invaluable expertise and access to his GPU. One thing I definitely pulled away from this project was how essential staying organized is. I had learned the lesson before and was mindful to stay organized this time, but I was simply unprepared for how quickly this project was going to expand. We went from naively anticipating we would train a single model that could identify positions effectively to all of a sudden having a pipeline of 2 stacks of 25 neural networks each alongside an array of pre and post processing steps. While this grew, I focused my mental resources on blasting through the hurdles that came our way, but I didn’t invest the time I wish I had afterwards of cleaning up our notebooks and building a streamlined process for doing everything. Overall an amazing project experience and certainly a highlight of my academic experience.

“Tactics flow from superior positions”

Bobby Fischer

One of the most important parts of improvement in chess is understanding the difference between strategic and tactical play. Just as with life, the need to accomplish certain goals requires varying levels of urgency. Let’s say you have a paper assigned you need to complete in a month: on the first day, you might be able to justify ignoring the looming task since you still have plenty of time to finish it. Maybe you could even wait a week? However after long enough, you’ll realize the lack of time you have and panic sets in. Maybe you put the entire paper off until the night before it’s due and, as a result, receive a failing grade on the assignment. You learn from the experience due to your poor time management and you learn useful tricks for approaching it differently in the future. Chess is no different! Being able to spot positions in which you have time or if the time has finally come for action to be taken is extremely important. Over time, you see many positions with different positional themes known as heuristics which guide your thought process which directly relates to your understanding of positional urgency.

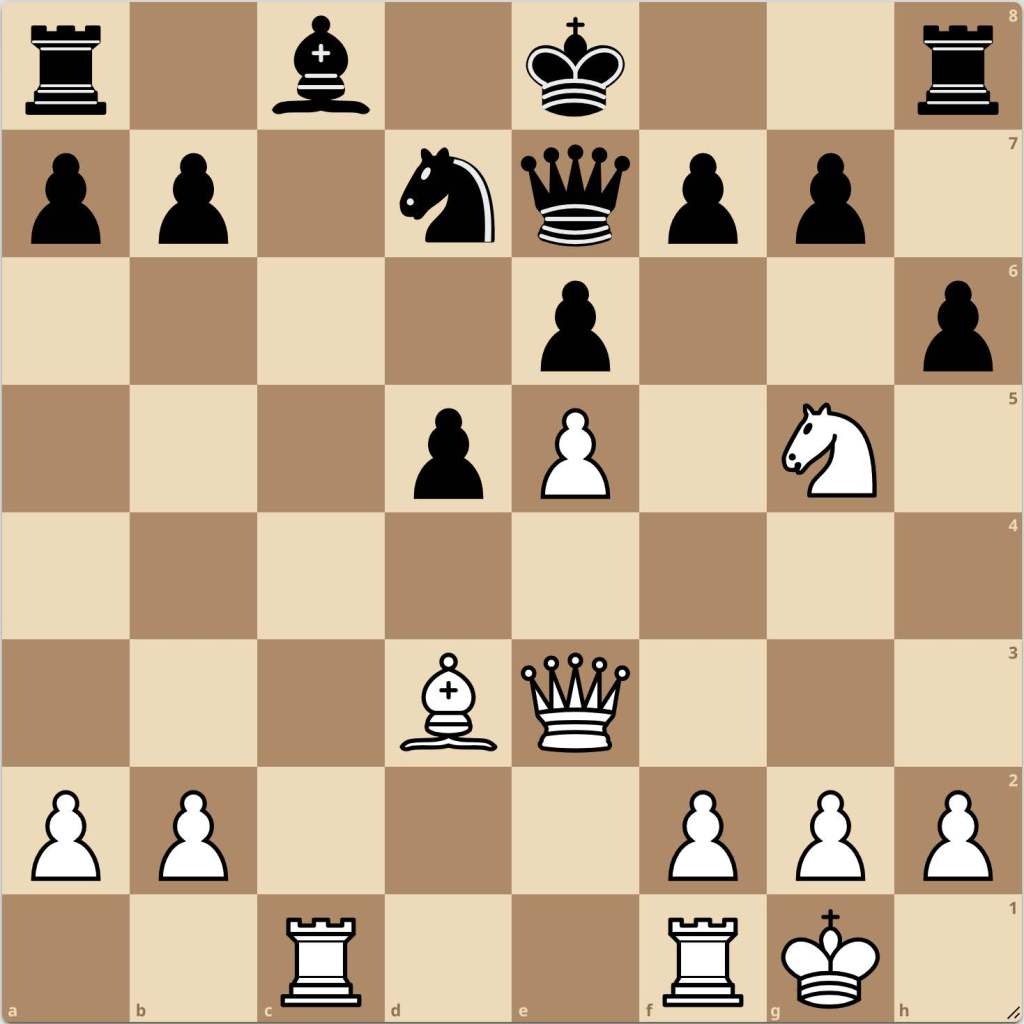

To understand this idea, evaluate the following position and reflect on your thought process as you do so:

Starting off simply, this is a very typical position involving an attack on the F7 pawn by the queen and bishop known as the Scholar’s Mate. This pattern is ingrained in us whether you’ve played it before or you’ve fallen for it yourself.. Now let’s consider a more difficult position. This is a position from none other than Magnus Carlsen playing as white in 2002 at only 11 years old against Tor Gulbrandsen. In the previous move, Gulbrandsen played h6, challenging Carlsen’s knight. Consider what you might do in this position and again, reflect upon your thought process. Which pieces immediately draw your attention? What advantage if any can be obtained here?

From this position, Carlsen played the spectacular move Qxa7, attacking the rook which really had no options. Gulbrandsen attempted to save his rook with …Rb8, however Carlsen again capitalized on the position with Qxb8, after which he achieved a satisfying victory. While the move may appear as one only a player as capable as Magnus Carlsen could play, it’s important to remember that in such a game as chess, these tactical motifs are always present, it’s only a matter of whether you can recognize them or not.

Heuristic vs Algorithmic Thinking

As part of understanding heuristics in chess, we will consider how standard chess-engines work. For traditional engines, there are two components: evaluation and search. The evaluation system consists of a predetermined set of weights which “evaluate” a single position based on factors such as material, space, and coordination among many, many other considerations. Search on the other hand is the engine’s ability to “look ahead” into the position at future states of the game with the evaluation function being applied to each of these future states. If you consider how good a computer is relative to its computing capacity, the best possible engine for its capacity is one which will be able to maximize the use of its resources for the most important lines to consider. Let’s say you apply a poorly optimized engine to the starting position and it wants to figure out the best move from the start. Without any guidelines for how it should use its resources, it will give equal consideration to all possible lines. There are 20 possible moves from the start and depending on what moves you make, the number of possible moves from each state will expand quickly. If we’re not careful, due to the exponential amount of resources required to evaluate any line, we will only be able to evaluate at a very low depth and thus will be quite poor. Therefore it’s essential that we be able to properly prune unnecessary lines so that we don’t waste resources investigating lines which are useless to consider.

In a blog post written by user likeawizard, he points out that to improve an engine’s capabilities while holding computational resources constant, you can either improve the algorithm for search or increase the speed with which you compute these calculations. If you add more constraints to your algorithm for considering moves, this will slow down your engine and because of the resources available, it will bottleneck and likely identify a suboptimal move.

As humans, we have our own form of pruning based on positional factors we associate with tactical and positional motifs. Specific lines which look more likely to possess tactical play draw our attention, and as our ability to visualize and calculate improves, players are able to more quickly determine the efficacy of a line.

Coming back to the position for the Carlsen-Tor match, Carlsen’s brilliant queen sacrifice is only considered brilliant because in order to see the line that Carlsen played, one must go beyond what is natural in such a position to find it. Now, while it’s possible to improve your tactical vision indirectly through game analysis and solving puzzles, we are working to create a new tool for users which will allow you to train this skill directly. To do this, users will be flashed a position and must successfully determine whether a tactic exists in the position or not.

Identifying Tactically-Charged Non-Tactical Positions

To accomplish our goal, we concluded that the best approach would be to train a series of neural networks to identify each type of tactic. A neural network is a form of machine learning which uses a series of interconnected neurons that work together to process information and learn over iterations of data observed, similar to the human brain. In order to input the chess positions into a format our model could interpret, we created an array of 12 8×8 matrices composed of 1’s and 0’s. Each matrix represents the position of a single piece type, one for white pawns, one for black rooks, etc.

Once we had our input, we had to decide on our model architecture. To keep things simple, we followed the approach of another similar project that also aimed to evaluate chess positions using neural networks without a search component. Their work was extremely useful to us and while we did experiment with other types of model architectures, like them we found no advantage to doing so. Our output layer consisted of 2 possible outcomes: whether the tactical theme in consideration exists or not.

During training, we were pleasantly surprised with the performance of many of our models. While the performance values didn’t necessarily mean anything to us yet because we would eventually be extrapolating our models to non-puzzles, it was reassuring to see that with relatively few training cycles, the models were capable of understanding the tactics at hand. After training the models, we applied them to pre-evaluated positions from lichess and this was the first position it found:

While this wasn’t perfect, it has clear elements which made it tactically intriguing (primarily Bd6+ which if Black responds with Rxd6 leads to Re8#). Some models were better than others which makes sense! For example, our models were excellent at identifying positions which had F2F7 attacking themes as they almost always involved a bishop and knight targeting the F2 or F7 square which the computer had no issue learning, while other tactic types such as hanging pieces and forks among others were problematic.

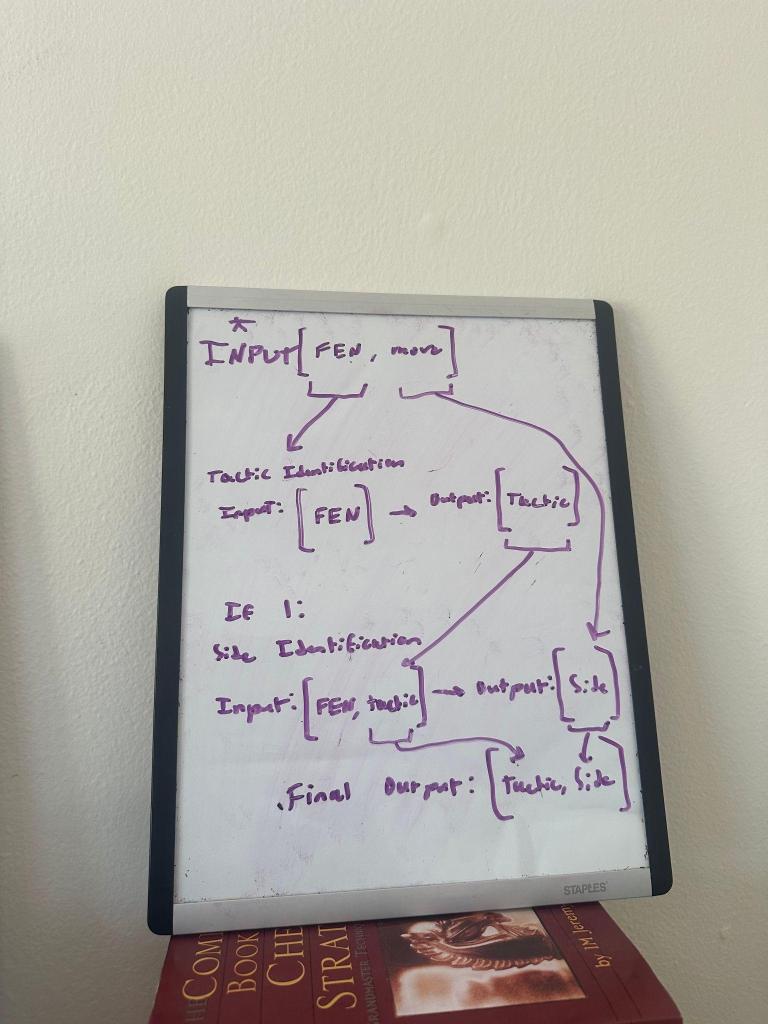

However, a funny edge case presented itself which we wouldn’t have otherwise expected: the tactic detection model was flagging positions as having a tactic, however the tactic that seemed present was actually for the opponent. Let’s say the model is shown a position where it is white to play. We naively assumed that the model would instinctively learn to classify which side the tactic was for based on whose move it was. This was evidently not the case.

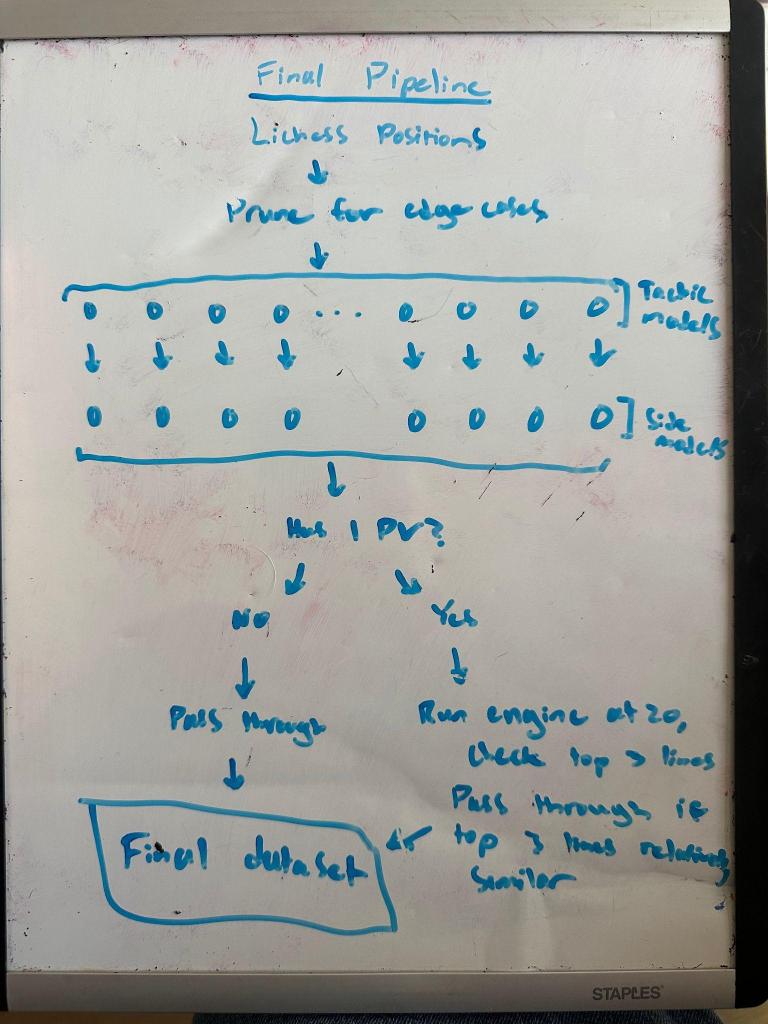

In order to remedy this issue, we had to have a way of determining which side the tactic was for if present. This led us to create another series of models, however this time they would be used to determine the side for which the tactic that existed was for. In order to generate the data we would use to train our dataset, we collected the entirety of the lichess puzzle dataset and labeled the data in accordance with the tactical theme they possessed as identified in the original data. This time we would pass through the position along with a binary value for if the tactic was for white or black for each individual type of tactic. Similar to the previous models, these were again quite accurate and as such our new pipeline looked as follows:

Now the important part of this was that we limited our possible positions to those which had an evaluation with an absolute value less than or equal to 150 centipawns. This is important as while our model pipeline is identifying tactics being existent, we can say with almost certainty based on the evaluation that a tactic does not exist (we’ll revisit almost soon…).

So in the end, our model would only flag positions which both flagged the tactic existing and that the tactic existed for the side predicted. However we encountered issues with a few of our models, particularly our fork model. For some reason, our fork model had a serious issue of extreme overclassification within our position data (it also featured among the worst accuracy rating on our testing set with 89% accuracy. This is obviously still good, just an interesting thing to note alongside the poor outside performance). Now this was a difficult issue to solve because we didn’t have convenient methods of addressing what the issue is in our data due to the fact that we’re applying the model to two separate sets of data. Thanks to the wonderful labeled data that we can train our neural nets on, we’re able to use these neural nets on unlabeled positions with neutral evaluations in order to obtain positions which are as empty in actual tactics as they are full with heuristical allure. By tricking our model, we sacrifice our ability to use typical model diagnostics since we can’t assume similarities between our training and applied data.

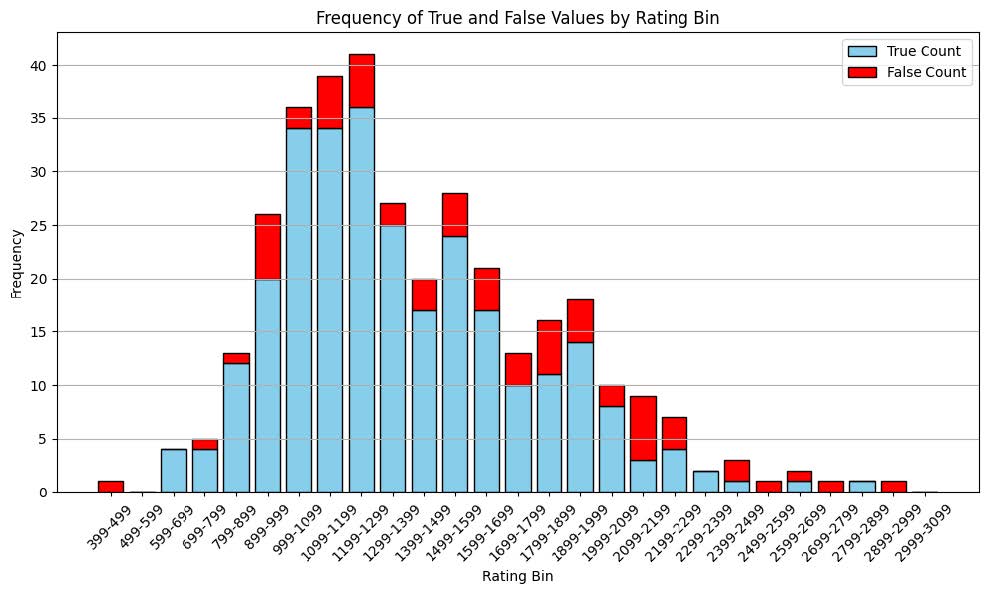

With that said, we began to dig into our dataset to understand the issue. Our theory initially was that complexity in the position might be an issue. To approach this, we decided to look at where our models were performing well versus not as good.

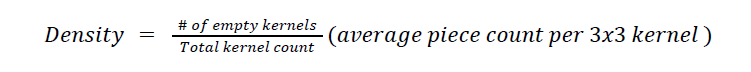

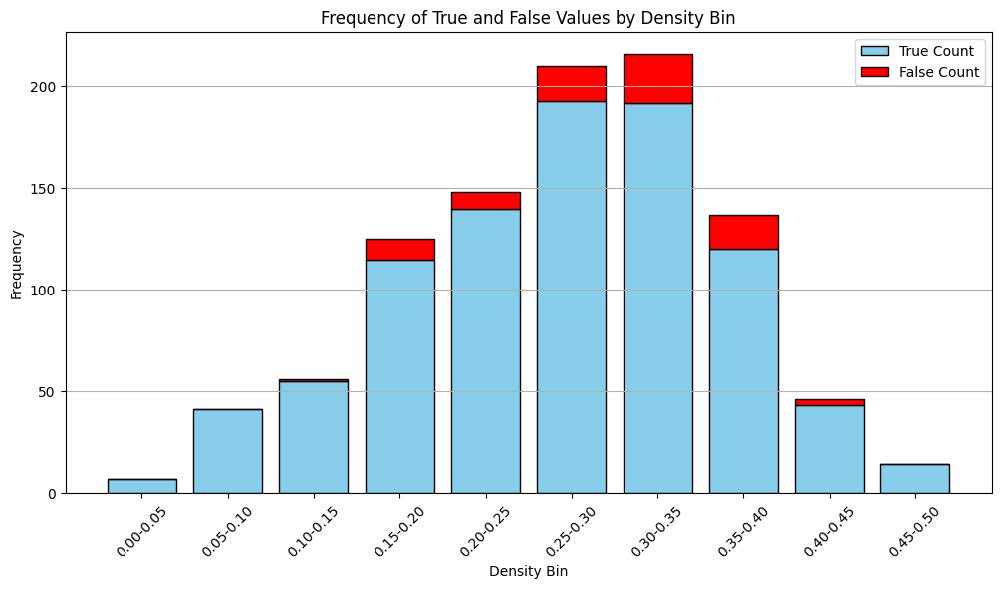

Well, if we break each respective bin and consider the proportion of positions correctly identified for each bin, we clearly see far better performance on lower-rated positions. Thus we refit the models using a larger proportion of lower-rated positions yet again, obtained a massive proportion of positions being flagged as forks which still did not appear as forks. As another attempt at finding a useful metric for analysis, we came up with a metric for piece density which we hoped would capture board complexity:

In order to properly consider density in a position, consider 2 positions, A and B, which both have an equal amount of material present. If A has more empty kernels present, then position A is more dense. This is because the same pieces in position A must be closer together if we have the same board and piece constraints.

While we noticed a slight left skew that seemed more pronounced among the false count, we concluded that the difference was inconsequential and thus was not worth investigating further.

One interesting thing we noticed was that many of the positions flagged as possessing a fork which we felt were poor positions to flag were often in the opening stage. To adjust for this, we again began to oversample positions in the middlegame and endgame which appeared to work for the time being! Many of the positions which we obtained looked more tactically interesting, and the ones it flagged in the opening seemed more fitting.

After adjusting the fork model, we began looking through our positions and identified a few specific edge cases were occurring:

- Positions with obvious captures which technically could count as a tactic

- Positions which were drawn by force

- Positions where either side was in check

- No material being on the board for whoever the tactic was for (only for pawn endgames)

The first was an interesting case, however it makes sense when you think about it according to the following hierarchy:

- The best line involves a capture on the next move;

- The piece being captured would be equal to the material imbalance of the position, and;

- The capture does NOT come with a check

This is a simple case usually in the middle of trading pieces which we had to algorithmically prune, although we made a conscious decision to keep positions which had a check given the first two conditions since sometimes those led to interesting positions and we wanted to reinforce the principle of always calculating forcing lines.

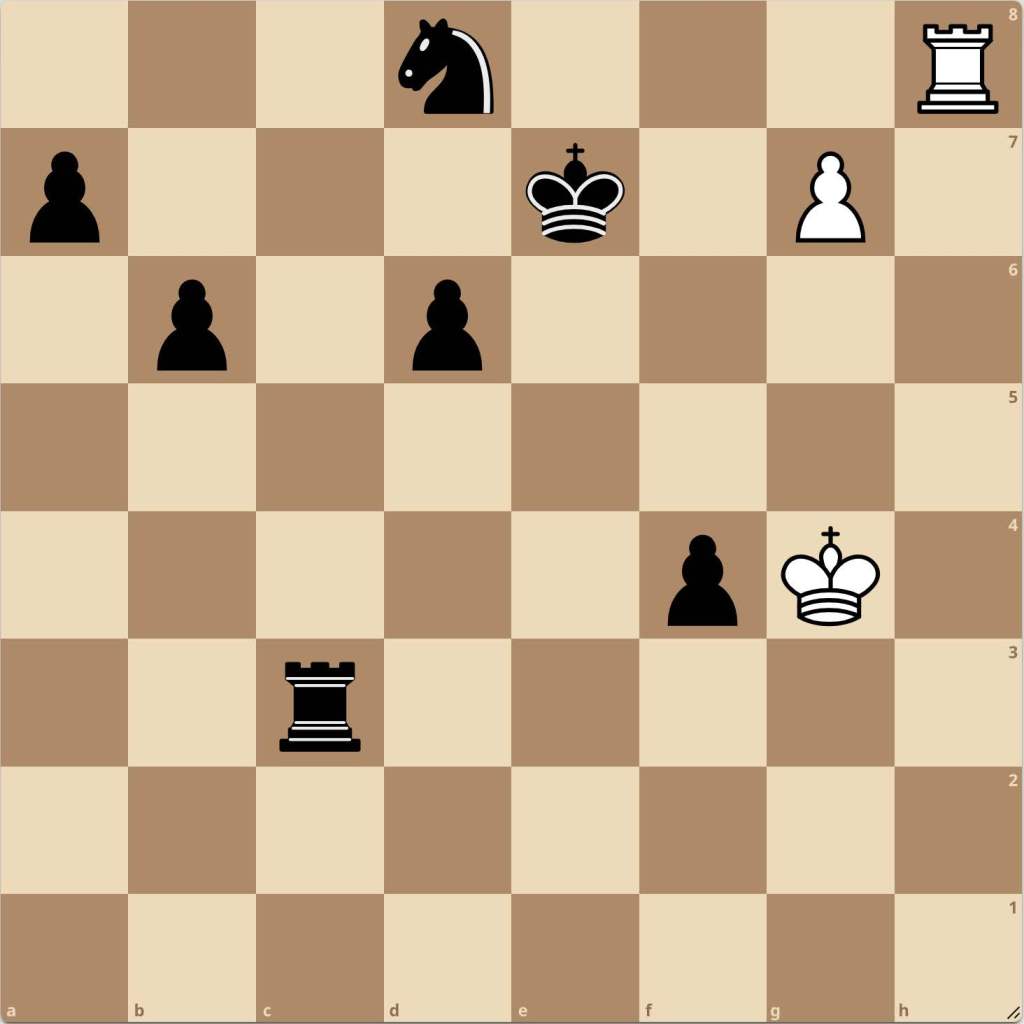

Now an important decision we made was to apply this pruning process first. It might seem as though we should eliminate these last, however it was surprising how many of the positions we had made up these positions. On samples of 1,000,000 positions usually 40% were pruned by this process. This allowed us to significantly decrease the number of positions that we were evaluating using our models, which saved us lots of time and computational resources. However even after such an extensive process, we still were running into problems. In particular, one example came to mind as especially problematic:

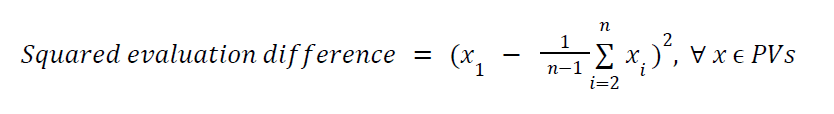

This position is technically a draw, however there is only a single line that actually leads to equality with the rest being considerably worse or dead lost. By this standard, this means that a tactic does actually exist since there is only a single line which leads to equality, therefore these are positions we should also be pruning for. Now in lichess’s evaluated positions dataset, the evaluations column is filled with multiple lines called principle variations, or PVs, based on how close the various best available lines are to the best engine line. We wanted to include only lines where the difference between the average evaluation of the lines past the top line is within a certain range. This is represented as:

Our goal with this metric is to calculate a custom variance metric. While variance is typically considered average squared difference from the mean, we’re not concerned with central tendency here and instead are concerned with the relation around the top-line evaluation.

This exponentially decaying behavior is continued, however changes once we consider mate positions (since an evaluation can provide either a CP value or a mate value depending on whether a forced checkmate is found).

Using this metric, we can identify positions where the squared average distance from the top line evaluation is between 0 and 10,000 (only want positions 100 centipawns in difference from top line). This ensures that for whatever reason the line is drawing, there isn’t too large of a difference between the other possible lines thus indicating a tactic doesn’t exist. Therefore, our final pipeline looks like:

Finally, we implemented a basic check for whether the top two lines were within 100 centipawns of each other. This allowed us to be aware of both the average difference of lines from the top line along with the difference between the top two lines. While difficult to quantify, the need for this as a feature was obvious when looking at positions. First of all, many of these positions with a lower squared evaluation difference possessed limited variability for a reason: they were boring. While our models had classified these positions as tactically interesting, the issue with these was that the ways in which they were interesting were very consistent. Many positions were endgames which visually do not look very tactically interesting along with many bland positions with common F2F7 themes which users were bound to learn quickly. Now many of the positions we were excited about were those with a higher squared evaluation difference, however as defined, these often had very erratic differences between the top line and the rest. Should these be allowed? Here’s the dilemma: if a position has one move which leads to a semi-equal evaluation while all others lead you to be semi-losing to lost, does that single move not constitute as a tactic of some type? Even though it doesn’t necessarily follow the same tactic motif that your eyes might be drawn to, by definition that IS a tactic.

Our thinking at the end of the day was that even though these positions had scenarios where you can go wrong, that should be a given. While the emphasis of our positions are those such that the position should be waving a cape in front of you, taunting your tactical awareness. In many of the positions which we observed, going for the tactic for which the position was labeled may result in a worse off position. In the end, we developed a consistent pipeline for finding tactically charged positions where no advantage exists. Let’s put this to the test:

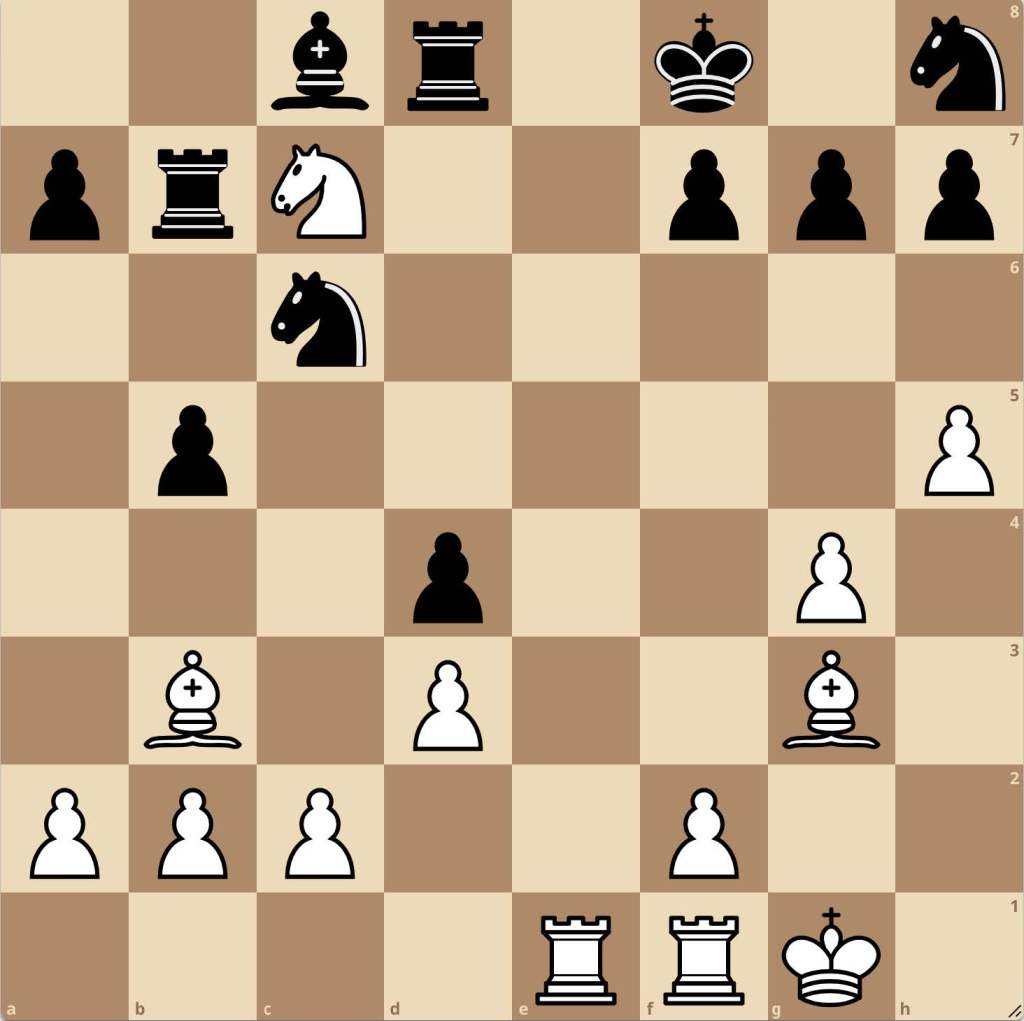

In the following position, it is black to move. The question you should ask yourself is if black is in fact winning due to some specific sequence of moves.

The answer is no! While a checkmate might appear present after playing …Ne2+, forcing the knight to be taken, white has only one move which survives: Kg2 after which Qh2+ is responded to with Kf3, escaping all checks. These types of moves are relatively difficult to spot as they involve us looking past the heuristic guidelines which might make many immediately not consider the option.

Using this process of assessing and pruning positions from lichess’s database of 66 million+ computer-evaluated positions, we are able to consistently collect large amounts of tactically interesting positions to be used for a platform designed to test a user’s abilities to identify whether or not a tactic exists in a tactically-complicated position.

Our neural network-based model, trained on chess positions with labeled tactical motifs, aims to sharpen this intuition for users. By distinguishing positions that are tactically charged but lack immediate advantage, our tool invites users to explore complex scenarios without predefined outcomes. As players test their instincts against these scenarios, they deepen their ability to discern tactical cues amidst positional play, bridging the gap between recognizing patterns and executing winning tactics.

Future Ideas: We envision developing a single metric—or a collection of metrics—that accurately scales the difficulty of a position, enhancing users’ experience by allowing for more personalized training. Additionally, we aim to create a feature that can identify and explain why a proposed tactic in a given position fails. This would offer players deeper insights into both positional resilience and tactical traps, promoting a more holistic understanding of chess strategy.

Leave a comment